Ménière's disease

| Ménière's disease | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

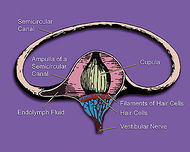

Inner ear |

|

| ICD-10 | H81.0 |

| ICD-9 | 386.0 |

| OMIM | 156000 |

| DiseasesDB | 8003 |

| MedlinePlus | 000702 |

| eMedicine | emerg/308 |

| MeSH | D008575 |

Ménière's disease (pronounced /meɪnˈjɛərz/[1]) is a disorder of the inner ear that can affect hearing and balance to a varying degree. It is characterized by episodes of vertigo and tinnitus and progressive hearing loss, usually in one ear. It is named after the French physician Prosper Ménière, who first reported that vertigo was caused by inner ear disorders in an article published in 1861. The condition affects people differently; it can range in intensity from being a mild annoyance to a chronic, lifelong disability.[2]

Contents |

Signs and symptoms

The symptoms of Ménière's are variable; not all sufferers experience the same symptoms. However, so-called "classic Ménière's" is considered to comprise the following four symptoms:[3]

- Periodic episodes of rotary vertigo or dizziness.

- Fluctuating, progressive, unilateral (in one ear) or bilateral (in both ears) hearing loss, usually in lower frequencies.[4]

- Unilateral or bilateral tinnitus.

- A sensation of fullness or pressure in one or both ears.

Ménière's often begins with one symptom, and gradually progresses. However, not all symptoms must be present for a doctor to make a diagnosis of the disease.[5] Several symptoms at once is more conclusive than different symptoms at separate times.[6]

Attacks of vertigo can be severe, incapacitating, and unpredictable and can last anywhere from minutes to hours[7], but no longer than 24 hours.[8] This combines with an increase in volume of tinnitus and temporary, albeit significant, hearing loss. Hearing may improve after an attack, but often becomes progressively worse. Nausea, vomiting, and sweating sometimes accompany vertigo, but are symptoms of vertigo, and not of Ménière's.[9]

Some sufferers experience what are informally known as "drop attacks"—a sudden, severe attack of dizziness or vertigo that causes the sufferer, if not seated, to fall without warning.[10] Drop attacks are likely to occur later in the disease, but can occur at any time.[10] Patients may also experience the feeling of being pushed or pulled. Some patients may find it impossible to get up for some time, until the attack passes or medication takes effect.

In addition to hearing loss, sounds can seem tinny or distorted, and patients can experience unusual sensitivity to noises.[11]

Some sufferers also experience nystagmus, or uncontrollable rhythmical and jerky eye movements, usually in the horizontal plane, reflecting the essential role of non-visual balance in coordinating eye movements.[12]

Migraine

There is an increased prevalence of migraine in patients with Ménière’s disease.[13] As well, migraine leads to a greater susceptibility of developing Ménière’s disease. The distinction between migraine-associated vertigo and Ménière’s is that migraine-associated vertigo may last for more than 24 hours.[8]

Cause

Ménière's disease is idiopathic, but it is believed to be related to endolymphatic hydrops or excess fluid in the inner ear.[14] It is thought that endolymphatic fluid bursts from its normal channels in the ear and flows into other areas, causing damage. This is called "hydrops." The membranous labyrinth, a system of membranes in the ear, contains a fluid called endolymph. The membranes can become dilated like a balloon when pressure increases and drainage is blocked.[15] This may be related to swelling of the endolymphatic sac or other tissues in the vestibular system of the inner ear, which is responsible for the body's sense of balance. In some cases, the endolymphatic duct may be obstructed by scar tissue, or may be narrow from birth. In some cases there may be too much fluid secreted by the stria vascularis. The symptoms may occur in the presence of a middle ear infection, head trauma or an upper respiratory tract infection, or by using aspirin, smoking cigarettes or drinking alcohol. They may be further exacerbated by excessive consumption of salt in some patients. Some have pointed out that this "central hypothesis" of Ménière's is questionable, as many people without Ménière's have evidence of increased pressure in the inner ear, too.

It has also been proposed that Ménière's symptoms in many patients are caused by the deleterious effects of a herpes virus.[16][17][18] Herpesviridae are present in a majority of the population in a dormant state. It is suggested that the virus is reactivated when the immune system is depressed due to a stressor such as trauma, infection or surgery (under general anesthesia). Symptoms then develop as the virus degrades the structure of the inner ear.

Ménière's typically begins between the ages of 30 and 60, and affects men slightly more than women. Hearing loss can affect both ears either simultaneously or with a variable interval between the first and the second ear.[19]

Other possible conditions that may lead to Ménière's symptoms include syphilis, Cogan's syndrome, autoimmune disease of the inner ear, dysautonomia, perilymph fistula, multiple sclerosis, acoustic neuroma, and both hypo- and hyperthyroidism.[20]

Diagnosis

Doctors establish a diagnosis with complaints and medical history. However, a detailed otolaryngological examination, audiometry and head MRI scan should be performed to exclude a tumour of the eighth cranial nerve or superior canal dehiscence which would cause similar symptoms. Because there is no definitive test for Ménière's, it is only diagnosed when all other causes have been ruled out. Because Ménière's, by definition, is idiopathic, one no longer has Ménière's disease if the cause of the symptoms has been discovered.[21]

History

Ménière's disease had been recognized prior to 1972, but it was still relatively vague and broad at the time. The American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery Committee on Hearing and Equilibrium (AAO HNS CHE) made set criteria for diagnosing Ménière's, as well as defining two sub categories of Ménière's: cochlear (without vertigo) and vestibular (without deafness).[22]

In 1972, the academy defined criteria for diagnosing Ménière's disease as:[23]

- Fluctuating, progressive, sensorineural deafness.

- Episodic, characteristic definitive spells of vertigo lasting 20 minutes to 24 hours with no unconsciousness, vestibular nystagmus always present.

- Usually tinnitus.

- Attacks are characterized by periods of remission and exacerbation.

In 1985, this list changed to alter wording, such as changing "deafness" to "hearing loss associated with tinnitus, characteristically of low frequencies" and requiring more than one attack of vertigo to diagnose.[24] Finally in 1995, the list was again altered to allow for degrees of the disease:[25]

- Certain - Definite disease with histopathological confirmation

- Definite - Requires two or more definitive episodes of vertigo with hearing loss plus tinnitus and/or aural fullness

- Probable - Only one definitive episode of vertigo and the other symptoms and signs

- Possible - Definitive vertigo with no associated hearing loss

Treatment

Because Ménière's cannot be cured, treatments focus more on treating and preventing symptoms.

Prevention

Some doctors recommend lipoflavonoids.[26]

Several environmental and dietary changes are thought to reduce the frequency or severity of symptom outbreaks. Most patients are advised to adopt a low-sodium diet, typically one to two grams per day.[6] Patients are advised to avoid caffeine, alcohol and tobacco, all of which can aggravate symptoms of Ménière's. Patients are often prescribed a mild diuretic (sometimes vitamin B6). Many patients will have allergy testing done to see if they are candidates for allergy desensitization, as allergies have been shown to aggravate Ménière's symptoms.[27]

Treatments aimed at lowering the pressure within the inner ear include antihistamines, anticholinergics, steroids, and diuretics.[6] Devices that provide transtympanic micropressure pulses (such as the Meniett) are now showing some promise and are becoming more widely used as treatments for Ménière's.[28] The Meniett, specifically, is proven to be a safe method for reducing vertigo frequency for a majority of users.[29]

The antiherpes virus drug acyclovir has also been used with some success to treat Ménière's Disease.[16] The likelihood of the effectiveness of the treatment was found to decrease with increasing duration of the disease, probably because viral suppression does not reverse damage. Morphological changes to the inner ear of Ménière's sufferers have also been found in which it was considered likely to have resulted from attack by a herpes simplex virus.[17] It was considered possible that long term treatment with acyclovir (greater than six months) would be required to produce an appreciable effect on symptoms. Herpes viruses have the ability to remain dormant in nerve cells by a process known as HHV Latency Associated Transcript. Continued administration of the drug should prevent reactivation of the virus and allow for the possibility of an improvement in symptoms. Another consideration is that different strains of a herpes virus can have different characteristics which may result in differences in the precise effects of the virus. Further confirmation that acyclovir can have a positive effect on Ménière's symptoms has been reported.[30]

Managing Attacks

Sufferers may be advised to take a specific drug, based on their needs, during an attack to curb symptoms. Typical remedies:[31]

- Antihistamines considered antiemetics such as meclizine and dimenhydrinate

- Antiemetic drugs such as trimethobenzamide.

- Antivertigo/antianxiety drugs such as betahistine and diazepam.

- Herbal remedies such as ginger root.[32]

Coping

Sufferers tend to have high stress and anxiety due to the unpredictable nature of the disease.[33] Healthy ways to combat this stress can include aromatherapy, yoga, T'ai chi.[34], and meditation.

Surgery

If symptoms do not improve with typical treatment, more permanent surgery is considered.[35] Unfortunately, because the inner ear deals with both balance and hearing, few surgeries guarantee no hearing loss.

Nondestructive

Nondestructive surgeries include those which do not actively remove any functionality, but rather aim to improve the way the ear works.[36]

Permanent surgical destruction of the balance part of the affected ear can be performed for severe cases if only one ear is affected. This can be achieved through what is effectively a chemical labyrinthectomy, in which a drug (such as gentamicin) that "kills" the vestibular apparatus is injected into the middle ear.[35]

Surgery to decompress the endolymphatic sac has shown to be effective for temporary relief from symptoms. Most patients see a decrease in vertigo occurrence, while their hearing may be unaffected. This treatment, however, does not address the long-term course of vertigo in Ménière's disease.[37] Danish studies even link this surgery to a very strong placebo effect, and that very little difference occurred in a 9-year followup, but could not deny the efficacy of the treatment.[38]

Destructive

Destructive surgeries are irreversible, and involve removing entire functionality of most, if not all, of the affected ear.[39]

The inner ear itself can be surgically removed via labyrinthectomy. Hearing is always completely lost in the affected ear with this operation.[6]

Alternatively, surgeons can cut the nerve to the balance portion of the inner ear in a vestibular neurectomy. Hearing is often mostly preserved, however the surgery involves cutting open into the lining of the brain, and a hospital stay of a few days for monitoring would be required.[40]

Vertigo (and the associated nausea and vomiting) typically accompany the recovery from destructive surgeries as the brain learns to compensate.[40]

Prognosis

Ménière's disease usually starts confined to one ear, but it often extends to involve both ears over time. The number of patients who end up with bilaterial Ménière's is debated, with ranges spanning from 17% to 75%.[41]

Some Ménière's disease sufferers, in severe cases, may end up losing their jobs, and will be on disability until the disease burns out.[42] However, a majority (60-80%) of sufferers will not need permanent disability and will recover with or without medical help.[41]

Hearing loss usually fluctuates in the beginning stages and becomes more permanent in later stages, although hearing aids and cochlear implants can help remedy damage.[43] Tinnitus can be unpredictable, but patients usually get used to it over time.[43]

Ménière's disease, being unpredictable, has a variable prognosis. Attacks could come more frequently and more severely, less frequently and less severely, and anywhere in between.[44] However, Ménière's is known to "burn out" to a stage where vertigo attacks cease over time.[45]

Studies done on both right and left ear sufferers show that patients with their right ear affected tend to do significantly worse in cognitive performance.[46] General intelligence was not hindered, and it was concluded that declining performance was related to how long the patient had been suffering from the disease.[47]

Notable cases

In history

- Alan B. Shepard, the first American astronaut, was diagnosed with Ménière’s disease in 1964, grounding him after only one brief spaceflight. Several years later, surgery (which was then at the experimental stage) was performed, allowing Shepard to fly to the Moon on Apollo 14.[48]

- Marilyn Monroe, American actress and cultural icon was known to experience the vertigo and compromised hearing associated with Ménière’s.[49]

- Charles Darwin may have suffered from Ménière’s disease.[50] This idea is based on a common list of symptoms which were present in Darwin's case, such as tinnitus, vertigo, dizziness, motion sickness, vomiting, continual malaise and tiredness. The absence of hearing loss and 'fullness' of the ear (as far as known) excludes, however, a diagnosis of typical Ménière’s disease. Darwin himself had the opinion that most of his health problems had an origin in his 4-year bout with sea sickness. Later, he could not stand traveling by carriage, and only horse riding would not affect his health. One of the diagnoses that he received from his physicians at the time was that of "suppressed gout". The source of Darwin's illness is not known for certain. See Charles Darwin's illness for more details.

- Martin Luther wrote in letters about the distresses of vertigo, and suspected Satan was the cause.[51][52]

- Julius Caesar was known to have suffered from the "falling sickness" as noted in Plutarch's Parallel Lives, and has been cited by Shakespeare, noting that Caesar was unable to hear fully in his left ear.[53]

- It has been suggested that Vincent Van Gogh, the Dutch Post-Impressionist, may have suffered from Ménière's,[54] though this is now considered conjectural.[55] See Vincent van Gogh's medical condition for a discussion of the range of possible alternative diagnoses.

- Jonathan Swift, Anglo-Irish satirist, poet, and cleric, is known to have suffered from Ménière’s disease.[56]

- Varlam Shalamov, a Russian writer, was affected.[57]

- Su Yu, PLA General who achieved many victories for the communists during the Chinese Civil War was hospitalized in 1949 and that prevented him from taking command in the Korean War, and Mao selected Peng Dehuai instead.[58]

In popular culture

- According to his blog, author and entrepreneur Guy Kawasaki has the illness.[59]

- J-pop singers Ayumi Hamasaki and Ai Kago[60] both sing despite suffering from Ménière's.

- Contemporary artist and graphic designer Doc Hammer, of The Venture Bros. fame, has Ménière's syndrome according to his May 16, 2005 journal entry.[61]

- Paddy McAloon, the singer and songwriter for the British pop group Prefab Sprout, was diagnosed with Ménière's in 2004.[62]

- Fictional comic book villain Count Vertigo suffers from Ménière's disease and has the ability to inflict its symptoms on others.

- In the Taiwanese drama Mysterious Incredible Terminator, the lead character 007 suffers from Ménière's disease.

- Fahrenheit singers Calvin Chen and Aaron Yan (who acted as lead character 007 in Mysterious Incredible Terminator) suffer from Ménière's disease

- Basketball player Steve Francis suffers from Ménière's.[63]

- The Cardinals singer Ryan Adams made it known he suffered from Ménière's disease when he announced his departure from the band.[64]

- Dawn Miceli, podcaster, discovered she may have Ménière’s disease while reading an article in Redbook.[65]

- Shawnae Jebbia, Miss USA 1998, was diagnosed with Ménière's disease while fulfilling her duties as Miss USA for the following year. Previously, she had a successful run as a fitness model/instructor on ESPN2, but this forced Jebbia into retiring from the entertainment business.[66]

- Singer and actress Kristin Chenoweth has performed on stage while suffering from severe symptoms of Ménière's disease. She wrote about her experience with Ménière's in her 2009 autobiography and talked about it on "Fresh Air with Terry Gross" in April 2009.[67][68]

- The disease was referenced in skit on Late Night with Jimmy Fallon on 8 August, 2009.

- Former NHL goaltender Zac Bierk has suffered from this disease since he was a member of the Peterborough Petes.

See also

- Balance disorder

- Neurectomy

- Superior canal dehiscence syndrome

- Tinnitus

Notes

- ↑ Dictionary.com Unabridged (v 1.1). Random House, Inc. Accessed on 9 September 2008

- ↑ Ménière's disease at Who Named It?

- ↑ "Meniere's disease symptoms". Mayo Clinic. 2008-06-18. http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/menieres-disease/DS00535/DSECTION=symptoms. Retrieved 2008-10-17.

- ↑ Haybach, p. 71

- ↑ Hazell, Jonathan. "Information on Ménière's Syndrome"". http://www.tinnitus.org/home/frame/meniere.htm. Retrieved 2007-02-27.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 "Meniérè's disease". Maryland Hearing and Balance Center. http://www.umm.edu/otolaryngology/menieres_disease.html. Retrieved 2008-03-03.

- ↑ Haybach, pg. 70

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Lempert, T.; Neuhauser, H. (November 2008). "Epidemiology of vertigo, migraine and vestibular migraine". Journal of Neurology 256 (3): 333–338. doi:10.1007/s00415-009-0149-2. PMID 19225823.

- ↑ Haybach, p. 72

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Haybach, pg. 90

- ↑ Haybach, pg. 79

- ↑ Haybach, pg. 46

- ↑ Lopez-Escamez, JA; Viciana D, Garrido-Fernandez P (June 2009). "Impact of bilaterality and headache in health-related quality of life in Meniere's disease". Annals of Otology, Rhinology and Laryngology 118 (6): 409–416. PMID 19663372.

- ↑ Haybach, pg. 8

- ↑ Menieres Causes a the American Hearing Research Foundation Chicago, Illinois 2008.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Shichinohe, Mitsuo (December 1999). "Effectiveness of Acyclovir on Meniere's Syndrome III Observation of Clinical Symptoms in 301 cases". Sapporo Medical Journal 68 (4/6): 71–77.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Gacek RR, Gacek MR (2001). "Menière's disease as a manifestation of vestibular ganglionitis". Am J Otolaryngol 22 (4): 241–50. doi:10.1053/ajot.2001.24822. PMID 11464320.

- ↑ Gacek RR (2009). "Ménière's disease is a viral neuropathy". ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 71 (2): 78–86. doi:10.1159/000189783. PMID 19142031.

- ↑ Margolis, Simeon (2004). The Johns Hopkins Complete Home Guide to Symptoms & Remedies. Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers. p. 550. ISBN 978-1579124021.

- ↑ Haybach, pg. 55

- ↑ Haybach, pg. 9

- ↑ Beasley, Jones, p.1111, para. 3

- ↑ Beasley, Jones, p.1111, para. 2/table I

- ↑ Beasley, Jones, p.1111, para. 4/table II

- ↑ Beasley, Jones, p.1112, para. 2/table III

- ↑ Williams HL, Maher FT, Corbin KB, Brown JR, Brown HA, Hedgecock LD (December 1963). "Eriodictyol glycoside in the treatment of Meniere’s disease". Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 72: 1082–101. PMID 14088725.

- ↑ Derebery MJ (2000). "Allergic management of Meniere's disease: an outcome study". Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery 122 (2): 174–82. PMID 10652386.

- ↑ Rajan GP, Din S, Atlas MD (2005). "Long-term effects of the Meniett device in Ménière's disease: the Western Australian experience". The Journal of laryngology and otology 119 (5): 391–5. doi:10.1258/0022215053945868. PMID 15949105.

- ↑ Gates GA, Verrall A, Green JD, Tucci DL, Telian SA (December 2006). "Meniett clinical trial: long-term follow-up". Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 132 (12): 1311–6. doi:10.1001/archotol.132.12.1311. PMID 17178941.

- ↑ Gacek RR (2008). "Evidence for a viral neuropathy in recurrent vertigo". ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 70 (1): 6–14. doi:10.1159/000111042. PMID 18235200.

- ↑ Haybach, p. 163

- ↑ Haybach, p. 198

- ↑ Haybach, p. 231

- ↑ Haybach, p. 198-200

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Haybach, p. 181

- ↑ Haybach, p.209

- ↑ Tsun-Sheng, Huang; Ching-Chen, Lin; Yun-Lan, Chang (1991). "Endolymphatic Sac Surgery for Meniere's Disease". Acta Otolaryngol 111 (S485): 145–154. doi:10.3109/00016489109128054.

- ↑ Thomsen, J; Bretlau, P.; Tos, M.; Johnsen, N.J. (1981). "Placebo effect in surgery for Meniere's disease. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study on endolymphatic sac shunt surgery". Acta Otolaryngol 107 (5): 558–61. PMID 6517150.

- ↑ Haybach, p.212

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Haybach, p.215

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Haybach, pg. 10

- ↑ Haybach, pg. 224

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Haybach, pg. 223

- ↑ Haybach, pg. 221

- ↑ Haybach, pg. 222

- ↑ Theilgaard, Laursen, Kjaerby, et al. p. 103

- ↑ Theilgaard, Laursen, Kjaerby, et al. p. 104

- ↑ Gray, Tara. "Alan B. Shepard, Jr.". 40th Anniversary of Mercury 7. NASA. http://history.nasa.gov/40thmerc7/shepard.htm. Retrieved 2008-03-03.

- ↑ Brown, Peter and Barham, Patte Marilyn: The Last Take. New York: Dutton, 1992, p. 221 ISBN 0-525-93485-5

- ↑ Hayman, John (2009-12-13). "Darwin’s illness revisited". BMJ 339: b4968. doi:10.1136/bmj.b4968. PMID 20008377. http://www.bmj.com/cgi/content/full/339/dec11_2/b4968. Retrieved 2010-05-22.

- ↑ Feldmann H (1989). "Martin Luther's seizure disorder" (in German). Sudhoffs Archiv 73 (1): 26–44. PMID 2529669.

- ↑ Cawthorne, T (1947). "Ménière's disease". Annals of Otology 56: 18–38.

- ↑ Cawthorne, T (1958). "Julius Caesar and the falling sickness". Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine 51 (1): 27–30. PMID 13518145.

- ↑ Arenberg IK, Countryman LF, Bernstein LH, Shambaugh GE (1990). "Van Gogh had Menière's disease and not epilepsy". JAMA 264 (4): 491–3. doi:10.1001/jama.264.4.491. PMID 2094236.

- ↑ Arnold, Wilfred N. (1992). Vincent van Gogh: Chemicals, Crises, and Creativity. ISBN 0-8176-3616-1

- ↑ Keith Crook, A Preface to Swift, p.6

- ↑ Toker, Leona (2000). Return from the Archipelago: narratives of Gulag survivors. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-33787-9.

- ↑ Su Yu (simplified Chinese wiki)

- ↑ "How to Change the World: The 10/20/30 Rule of PowerPoint". http://blog.guykawasaki.com/2005/12/the_102030_rule.html.

- ↑ Ai Kago; B.Slade & Kuno (translators). "Kago Ai Official Blog: Translations 2008.11.13 - 2008.11.19". http://www.hello-online.org/index.php?act=helloonline&CODE=article&topic=593. Retrieved 2008-11-20.

- ↑ "50 Questions (from MySpace)". 2005-05-16. http://doc-hammer.deviantart.com/journal/.

- ↑ "sproutnet :: about the band". http://www.prefabsprout.net/about.html.

- ↑ "Down-shifting: with encouragement from the anxious Rockets, Steve Francis is restricting his high-flying game to reduce the risk of a crash landing". Findarticles.com. http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m1208/is_49_226/ai_95107202. Retrieved 2008-12-25.

- ↑ "Ryan Adams Saga Continues". January 15, 2009. http://www.relix.com/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=3635&Itemid=3635. Retrieved 2009-01-15.

- ↑ Dawn and drew show episode 851

- ↑ "Bouncing Back from Hearing Loss". Fox News. n/a. http://video.aol.com/video-detail/bouncing-back-from-hearing-loss/2047534284. Retrieved 2009-06-19.

- ↑ Chenoweth, Kristin (April 2009). A Little Bit Wicked: Life, Love, and Faith in Stages. Touchstone. ISBN 1416580557.

- ↑ Terry Gross (April 16, 2009). "Kristin Chenoweth Is 'A Little Bit Wicked'" (link to audio). Fresh Air. WHYY-FM. http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=103147489. Retrieved 2009-04-16.

References

- Theilgaard A, Laursen P, Kjaerby O, et al (1978). "Menière's disease. II. A neuropsychological study". ORL J. Otorhinolaryngol. Relat. Spec. 40 (3): 139–46. PMID 570693.

- Beasley NJ, Jones NS (December 1996). "Menière's disease: evolution of a definition". J Laryngol Otol 110 (12): 1107–13. doi:10.1017/S002221510013590X. PMID 9015421.

- Haybach, P. J. (1998). Meniere's Diease: What You Need to Know. Portland, OR: Vestibular Disorders Association. ISBN 0-9632611-1-8.

External links

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||